Perhaps any technology born for war and covert surveillance was fated to struggle in its attempt to make a transition to domestic life. That is certainly the case for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or unmanned aerial systems (UAS), better known as “drones,” which are experiencing an arduous journey from foreign battlefields to the public airspace in the United States.

For the U.S. military, drones provide an economical alternative to manned raids in the dangerous enterprise of collecting intelligence and hunting terrorists. In the popular imagination, drones conjure up an image of stealth, of secret incursions targeting terrorists and enemy combatants in foreign lands. Yet the devolution of UAVS from military/intelligence tools into peaceful domestic products has been proceeding at a rapid pace.

Recent revelations that the National Security Agency is engaged in data mining that includes surveillance of U.S. citizens, and that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the U.S. Border Patrol all use drones in domestic airspace have alarmed civil libertarians who regard such tactics and technology as an Orwellian threat to basic freedoms and a violation of the Fourth Amendment. Their apprehensions have been heightened by the production of technologically advanced drones that can be shrunk to the size of a quarter—with infrared cameras, sensors that spot movement, and automatic license plate readers, the next generation of UAVs will be able to easily go places that prying eyes have been unable to visit in the past.

“There is something visceral about being watched,” says Clifford S Fishman Professor – Columbus School of Law. “That’s direct. It bypasses the brain and goes straight to the emotion. That’s why drone surveillance strikes fear in people a lot more than electronic acquisition of data by private companies or the government.”

Public polls confirm this observation. A June 2012 Monmouth University poll found that four out of five Americans have privacy concerns regarding the ability of law enforcement to use drones equipped with high-tech cameras, and an overwhelming majority of citizens do not want UAVs used to catch speeding drivers on our freeways.

Like most advanced technologies, the pace of drone development has exceeded the pace of the law. Innovations in drone technology and their commercial application are pressing the limits of privacy statutes. Experts see years of jurisprudence ahead to set the legal limits for commercial drone use.

“To me, there’s not a lot of legal work around drones yet,” says Marc Zwillinger, founder and managing member of ZwillGen PLLC, and an expert in privacy and electronic communications. “It’s a question of figuring out what the law would say now if we just applied the standard Fourth Amendment principles for government and standard privacy principles for the private sector.”

States have tried to apply the brakes on domestic drones, introducing more than 80 bills to regulate or ban the commercial use of UAVs. Meanwhile, Congress has held a series of hearings to investigate privacy and safety issues, but there is little movement to regulate commercial drones other than requiring the FAA to plot a route for their domestic lift-off.

Recognizing the challenges ahead, and the refusal of state legislatures to be restrained on the issue, the drone manufacturing community and many of its amateur hobbyists and proponents are reaching out to privacy and safety advocates to find a way to live with drones without tearing apart privacy protections or ignoring legitimate safety concerns. It’s an effort that all sides hope will succeed, especially given the fact that drones aren’t likely to disappear anytime soon.

A Checkered Past

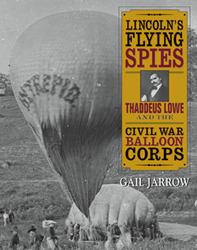

Aerial surveillance is not a recent phenomenon. In fact, its infancy dates back to the Civil War when both the Confederate and Union forces used hot air balloons to scout each other’s troops. Surveillance efforts were appreciably advanced before and during World War I when scientists and engineers worked to develop mechanized drones for reconnaissance and later for attack missions. Kinks in the system, however, kept drones from widespread deployment.

By World War II, many of the engineering problems appeared solved, and the military launched Operation Aphrodite (U.S. Army Air Forces) and Operation Anvil (U.S. Navy). They used aircraft that had been taken out of service and loaded them with explosives to target fortified German bunkers. (The aircraft would take off under human control, and once airborne, the flight crew would bail out and the plane would be guided to its target by remote radio control.) Despite the effort, the drones kept missing their targets, crashing, or being shot down, and both programs were eventually suspended.

By World War II, many of the engineering problems appeared solved, and the military launched Operation Aphrodite (U.S. Army Air Forces) and Operation Anvil (U.S. Navy). They used aircraft that had been taken out of service and loaded them with explosives to target fortified German bunkers. (The aircraft would take off under human control, and once airborne, the flight crew would bail out and the plane would be guided to its target by remote radio control.) Despite the effort, the drones kept missing their targets, crashing, or being shot down, and both programs were eventually suspended.

Drone development continued throughout the Cold War, but it wasn’t until the Vietnam War that the public first learned of the widespread use of drones on the battlefield. They proved exceptionally adept at reconnaissance photography as well as in deploying smart bombs. They also earned the colorful nickname “Bullshit Bombers” when they were used to drop propaganda leaflets on Vietnamese villages.

Of course, today’s drones are far more technologically advanced than the UAVs used in the skies over Vietnam. Sophisticated imaging technology, such as gigapixel cameras, allows drones to provide real-time video and track targets over vast distances with astonishing accuracy and speed. From the size of a hummingbird to the heft of a 737 airplane, drones can be employed for any number of tactical operations. Beyond battlefields, drones are already tasked with a number of potentially risky chores here at home: Patrolling the U.S.–Mexico border, tracking hurricanes, firefighting, and inspecting high-tension wire electrical towers, to name a few.

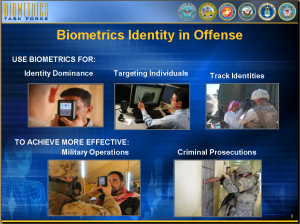

But their greatest value, many believe, is in surveillance. When drone cameras are equipped with facial recognition software and linked to massive government databases, such as the FBI’s Next Generation Identification program or the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Automated Biometric Identification System, their reach is astounding. Biometric identifiers include fingerprints, iris scans, voice data, and face-recognition-ready photos.

It’s a chilling notion for some civil liberties and privacy groups. Industry leaders say “that drones do not operate in a vacuum, noting that they are not runaway machines without a legal or moral compass behind them. Most drones are carefully guided systems that include the vehicle itself, its payload, a communications package, a ground station, and a human being determining its mission.”

Michael Toscano, president and chief executive officer of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), the drone manufacturers’ lobbying group, believes that focusing on drone hardware and payload ignores a critical element of the system—its human brain and judgment.

“There is accountability with a human being,” Toscano said during the forum “The Drone Next Door,” sponsored by the New America Foundation in May. “Someone is always operating the system anytime you see any of these things flying.”

“They are an extension of the eyes and ears and hands of a human being, that allow them to do those dirty, dangerous, difficult and dull missions out there,” said Toscano.

High–Tech Killing Machines

While the military uses drones for everything from reconnaissance to delivering supplies, UAVs receive the most attention for their role as killing machines. The first known targeted killing by a U.S. drone was in February 2002. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) used a Predator drone to launch a Hellfire missile in Afghanistan to take out someone who was “thought to be” Osama bin Laden. The effort was for naught; it wasn’t bin Laden.

“If this were a traditional kind of war, like World War II, and we developed drones to engage in targeted killing of individual German soldiers or leaders, nobody would be complaining, especially because it causes minimal collateral damage,” says John B. Bellinger III, a partner in the national security and public international law practices at Arnold & Porter LLP. “Critics agree that targeted killing or extrajudicial killing would be perfectly acceptable in traditional war, but their premise is this is not a traditional war. For them, these targeted killings or extrajudicial killings are really illegal. That’s where the debate really stands.”

Between 2004 and 2013, the CIA launched an estimated 400 to 500 drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, killing more than 4,000 people, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, an independent, not-for-profit fact-finding organization in the United Kingdom. The bureau reported that between 400 and 950 civilians were killed in those strikes, including as many as 200 children. Those figures are a far cry from the total number of strikes, casualties, and injuries associated with U.S. drone missions because they do not include the military’s efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq, where drone strikes are pegged at more than 1,500.

Congressional deliberations on UAV strikes and killings will continue on Capitol Hill and internationally for some time to come, or at least until the United States stops using drones to kill enemy combatants. In March U.S. Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.) drew headlines with his nearly 13–hour filibuster of John Brennan’s nomination as CIA director. In doing so, he stoked the outrage of the Obama administration with his public suggestion that the U.S. government could use drones to target Americans on U.S. soil.

Paul said it was a letter from U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder that prompted his filibuster. In that letter, Holder said: “It is possible, I suppose, to imagine an extraordinary circumstance in which it would be necessary and appropriate under the Constitution and applicable laws of the United States for the President to authorize the military to use lethal force within the territory of the United States.”

Enter the filibuster. After Paul made his point, Holder wrote him again, but this time the response was brief and to the point: “It has come to my attention that you have now asked an additional question: ‘Does the President have the authority to use a weaponized drone to kill an American not engaged in combat on American soil?’ The answer to that question is no.”

Yet there remains some debate about whether or not that is true. Holder’s letter may reflect the president’s “position,” though many believe it is not right on the legal question. Bellinger and others suggest that law enforcement in the United States, including “the president, has the power to kill someone if he or she poses a threat or danger to the public.”

“The president does have the authority to use a drone to kill someone inside the United States just the way law enforcement can use lethal force if “someone posed an imminent threat,” Bellinger says. “If somebody is driving a gas tanker truck at 100 miles an hour down the road to crash it into the Hoover Dam, the police can shoot that person to stop him. The same would be true with a drone.”

But industry officials say the law prevents commercial UAVs from being equipped with the tools to complete such a mission. “The FAA says no aircraft, manned or unmanned, can deploy any weaponization “at this time,” [ That is simply NOT true!] Toscano said during the May forum on drones. In the United States, it is “breaking the law, and if you break the law, you should be held accountable.”

What, exactly, does the Obama administration mean by “engaged in combat”? The extraordinary secrecy of this White House makes the answer difficult to know. Here are some clues, and they are troubling.

If you put together the pieces of publicly available information, it seems that the Obama administration, like the Bush administration before it, has acted with an “overly broad definition” of what it means to be engaged in combat. Back in 2004, the Pentagon released a list of the types of people it was holding at Guantánamo Bay as “enemy combatants” — a list that included people who were “involved in terrorist financing.”

One could argue that that definition applied solely to prolonged detention, not to targeting for a drone strike. But who’s to say if the administration “believes in such a distinction?” For example: National Defense Authoriation Act (NDAA).

Non–Lethal Uses

While UAVs can play a clear role in law enforcement and public safety, they also can provide assistance in any number of industries, including entertainment, transportation, oil and gas, and cargo hauling, if allowed to operate in the public airspace.

In fact, some environmental groups and federal agencies are already using drones to revolutionize the process of monitoring the health of oceans, forests, wetlands, and wildlife. “We’re looking at UAS technology as just another observing system to come into the other larger observing systems we’re already using,” said Robbie Hood, director of the Unmanned Aerial Systems Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), at the New America Foundation–sponsored forum. “We want to take these technologies” and rapidly deploy them for scientific purposes, Hood added.

Along with satellites, ocean buoys, and rain gages, NOAA would use drones to track everything from high-impact weather to marine wildlife to illegal fishing in U.S. waters. Hood said drones could be instrumental in helping scientists to learn more about storm systems as they’re coming over the ocean or in studying the effects of climate change in the Arctic.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), an international wildlife conservation group, is applying that philosophy in using drones in Africa and Nepal to monitor endangered species such as elephants, rhinoceros, and tigers, all of which are threatened by poaching. WWF is hoping to employ drones more widely to alert local governments to poachers at night when they sneak across borders to kill endangered animals.

“We are so outmatched technologically that anything we can bring to bear on this is welcome,” WWF President and Chief Executive Officer Carter Roberts said at the same forum. Another critical role for drones is securing data about animals and their ecosystems, which can be used to protect species from extinction, according to Roberts. “We do not want to document the demise of nature,” Roberts said. “We want to engage decision makers when there is still time, when nature is still intact.”

The needs of the environment and agriculture could dovetail in another critical area for drone use: precision pesticide spraying. Targeted spraying in distant fields may help farmers to more carefully apply pesticides and “limit” their runoff into nearby streams.

“What’s happening right now is kind of a quiet revolution,” Mary “Missy” Cummings, a former U.S. Navy aviator and an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the audience at the New America Foundation forum. “Drones are revolutionizing agriculture. . . . This is a community that absolutely needs it for the bottom line.”

Some 7,500 drones could be in commercial use in the next five years, according to the FAA. The AUVSI estimates that the UAV industry could create up to 100,000 new jobs and add some $82 billion in economic activity to the U.S. economy between 2015 and 2025.

Competing in Crowded Skies

Integrating drones into the U.S. airspace will be challenging, although not impossible, experts say. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 charged the agency with deciding how best to incorporate smaller drones without creating a risk to people or property. The FAA is tentatively scheduled to release draft rules by mid-October, followed by a four-month comment period.

Additionally, the FAA will select six sites by December to begin gathering data from test flights of smaller drones—UAVs that stay below an altitude of 400 feet and weigh less than 55 pounds. The FAA has so far received 50 proposals from 37 states in the race to become a drone test site.

For many air transportation experts, the future of commercial drone use comes down to safety. That there are supreme safety concerns involved in adding tens of thousands of drones, even small ones, into the United States’ already crowded skies is the central reason Congress tapped the FAA for this mission.

“Our air traffic control system and our whole air transportation system [are] extraordinarily safe in the United States,” says David Kirstein, a partner at Kirstein & Young, PLLC, which specializes in aviation law and policy. “If you apply the same rules to drones that you do to general aviation, if not commercial aviation, then they can eventually do this in a safe way. I don’t think it’s going to happen next week or next year. We’re probably at least five years away from significant use of commercial drones in the United States.”

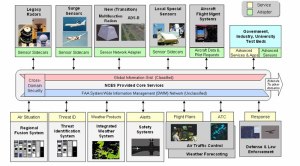

Kirstein believes the real challenge for the FAA in licensing commercial drones is in finding a happy medium between allowing some legitimate uses of drones while also keeping heavily congested airspace around cities and airports free of UAVs. Most drones are not equipped with sense-and-avoid devices to alert other aircraft to their presence, a critical factor in commercial flight.

“The FAA may have to wait to bring them into commercial airspace until the NextGen systems are up and running and “proven reliable,” says Kirstein, referring to the FAA’s soon-to-be-deployed, high–technology Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen). “That way, people in piloted aircraft will be able to maneuver out of the way and contact air traffic control about drones when they’re spotted.”

Another concern is one that is associated with any electronic system in use today: hacking. Today it is almost impossible to create a hack-proof system, and there are real dangers if criminals or terrorists—or even 14-year-old programming geeks, for that matter—hack into the communications system of a drone by accident or on purpose and change its course.

“Hacking happens,” Cummings said at the May forum. “Any electronic device can be hacked. Period. You have to live with it. We’ve known that for some time.”

The FAA will “likely” address that and other concerns with rules requiring a rigorous maintenance process for UAVs, much like the one used by commercial airlines that mandates regular system reviews and periodic overhauls.

As the rulemaking procedure moves forward, the FAA continues to certify some drones for use today. Over the last few years it has issued hundreds of certificates to police, federal government agencies, and universities and research institutions authorizing drone use. Most of the uses are narrowly focused on law enforcement and research, but no one can know for sure because the FAA does not disclose those agencies or institutions that have obtained certificates. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an electronic privacy rights group, has sued the FAA to obtain those certificates to find out whether the institutions and agencies granted permits have privacy protections in place.

What is known is that at police agencies are using drones in their field operations, and more have asked the FAA for permission to deploy them. The Miami–Dade Police Department, which received the first FAA permit to fly a robotic plane, uses a small drone to survey crime scenes.

Mr. Williams of the FAA’s dismissed privacy concerns, saying, “The FAA has no authority to make rules or enforce any rules relative to privacy.”

“We can ask [the industry] to take into consideration the privacy issue. … There aren’t any rules to date on that.”

Industry and privacy groups also are likely to disagree on another key factor in the debate: Reforming the certification process. Industry officials are hoping the FAA will streamline the certification procedure to make it easier for drone operators to be licensed. The change would conveniently mix with the creation of the new rules for commercial drones. Safety and privacy experts, however, say the rules should be strengthened, not weakened, especially because the public should be protected from the onslaught of UAVs post-2015.

Watching the Watchers

Limiting the use of drones is becoming a cottage industry among the states, with legislators battling back efforts by police and industry groups to expand the use of UAVs once the FAA gives the green light for commercial drone use.

More than 80 bills or resolutions have been introduced in 42 states, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The proposed laws are as varied as the states. Some states want to ban efforts to attach weapons to drones, while others want to require police to obtain a warrant first before using drones for surveillance. Still others would allow people to sue for damages if drones illegally tracked them.

Six states—Florida, Idaho, Montana, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia—have already enacted laws addressing drone use. Virginia has created a two-year moratorium on law enforcement use of drones to allow more time to study the issue, while Florida and Idaho require police to obtain permission from a judge before using drones. The laws in Montana and Tennessee reflect that same approach.

The Texas statute, which has been disparaged by both sides, takes a crazy–quilt approach to drone regulation. It bans “most” private uses of drones, but specifies 19 exceptions that reflect industry considerations. For example, realtor’s can use drones to take photos of property, and oil companies can use them to monitor their rigs.

An initiative spearheaded by the Aerospace States Association could prove to be the best way forward to forestall 51 different approaches to drone regulation in the United States. The initiative brings together all the parties, including the AUVSI, the ACLU, and the EFF, to create model legislation that addresses privacy concerns while keeping the drone industry viable by avoiding moratoriums on drone use. Two of the most critical members of the task force are the Council of State Governments and the National Conference of State Legislatures, which represent state executives and legislators, respectively. The group hopes to finalize the draft legislation by September.

“Our system of government is designed so the states can pass laws that may vary from state to state and see what works best,” says Jennifer Lynch, a staff attorney at the EFF. “That may be the best approach given how difficult it is to pass anything through Congress these days. It would be better to have a national privacy law instead of a patchwork of state laws, but who knows how long we’d have to wait for it?”

The EFF has offered state and federal lawmakers some guidance on how best to regulate drones. They encourage officials to follow three principles: Law enforcement must obtain warrants to use drones in investigations; commercial drone operators must disclose the details of their operations and comply with current privacy requirements; and legislation must strike a balance between privacy rights and free speech.

Aside from the traditional partisan gridlock, there is no clear consensus on drones in Congress. Lawmakers in both chambers have held hearings on domestic drone use in the last six months, focusing specifically on privacy rights. Legislation is pending in both houses of Congress, though few expect it to go anywhere before the FAA issues regulations on integrating drones into the national airspace. There is an effort, however, to have Congress speak before drones become an issue for the courts.

“It seems to me that Congress needs to set the standard, rather than wait and let the courts set the standard,” said U.S. Rep. Ted Poe (R–Tex.) during a House Judiciary subcommittee hearing in May. Poe has coauthored the bill Preserving American Privacy Act of 2013, which makes it illegal to arm a drone in U.S. airspace and requires police to have “probable cause” and a warrant to search a “non-public area using a drone.”

In the Senate, Paul introduced a bill in May to require law enforcement to obtain a warrant to use drones for surveillance, except to protect lives, fight terrorism, or to patrol the nation’s borders. Under the bill, Americans could sue the government for violating the act.

Congress remains in a holding pattern of sorts. Many members still seem to be trying to wrap their arms around a technology that is changing daily and presenting new challenges as it changes. At a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in March, U.S. Sen. Al Franken (D–Minn.) marveled at the fact that drones are getting smaller.

“Presumably at some point [Too late. There already in place] you could have one the size of a mosquito that has a battery that operates for weeks and you could have the mosquito following you around and not be aware of it,” Franken said. “God help us if an adolescent boy gets hold of one of these.”

Growing Privacy Concerns

When it comes to drones and privacy, the crux of the debate is how best to protect Fourth Amendment rights in the face of a new and evolving technology that also happens to bring enormous benefits. And what really worries many foes of drone integration is how that technology could be linked to other more invasive tools to further intrude on civil liberties.

“Some of the things that drones are capable of doing are pretty amazing and beneficial to society,” Lynch says. “Environmental and human safety savings we get from drones are important, but those are very different uses than law enforcement uses. That’s where we need to think very clearly about the ramifications of this technology.”

Many observers are uncertain whether existing legal protections that guard an individual’s right to privacy concerning other technologies will be effective or even pertain to violations from drone use.

“The biggest problem with drones is figuring out how to apply the fair information and privacy practices to them,” Zwillinger says. “The idea behind those practices is notice and choice. When you collect information on people, you give them notice and some sort of choice to opt out in the private sector. How do you apply that to drones? How do you give people notice that drone surveillance is going on? Does it have to say it on the side of the drone?”

That’s where some kind of rigorous system of reporting might be useful to the public, privacy advocates say. “When you license drones, you’re in a position to require drone operators to turn over information about surveillance and their technology, and what they plan to carry on the drone and where they plan to operate,” says Amie Stepanovich, director of the Domestic Surveillance Project at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a privacy watchdog group.

Others say current protections afforded to individuals under the Fourth Amendment are sufficient to cover any concerns about privacy. Gregory S. McNeal, an associate professor at Pepperdine University School of Law, told a House Judiciary subcommittee hearing in May that it is unnecessary to require warrants for surveillance.

McNeal encouraged lawmakers to treat information gathered by drones as they would information collected by police sitting in a police car and observing a neighborhood. He also urged them to reject broadly worded drone use restrictions and to carefully define terminology, because terms of art in the law may have different meanings in the public square.

“Such a technology–centric approach to privacy misses the mark—if privacy is the public policy concern, then legislation should address the gathering and use of information in a technology-neutral fashion,” McNeal said at the hearing titled “Eyes in the Sky: The Domestic Use of Unmanned Aerial Systems”

Privacy advocates say it’s a false comparison to liken drones to police cars or stationary cameras. Drones are stealthier and can get closer to a subject, while police may be forced to keep their distance and stationary cameras cannot follow people home and into their backyards. “We recognize that aerial surveillance is not new, but drones do change it by allowing more of it to happen,” Stepanovich says.

And while there is much talk about how the courts could and should handle cases involving drones and privacy, there is no certainty that drones will fit within prevailing jurisprudential analysis. There are three U.S. Supreme Court cases on aerial surveillance and tracking that likely could have some sway on lower courts.

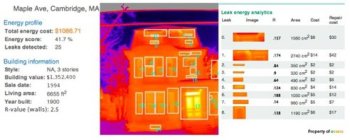

In California v. Ciraolo, the justices concluded in 1986 that police officers did not need a warrant to use information gained by an airplane flying over the individual’s fenced property because it was visible to the naked eye. The Supreme Court in later rulings began to see dangers associated with new surveillance technologies. In its 2001 ruling in KYLLO V. UNITED STATES, the justices determined that surveillance of a home using a device not in general public use, such as a thermal imaging device in this case, constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment. Finally, in 2012, in UNITED STATES v. JONES, the justices found that a person’s privacy was violated when police attached a GPS tracker to a car and monitored its movements for four months.

From Automated to Autonomous

As lawmakers and judges ponder what to do with commercial drones and privacy and safety concerns, the evolving technology of UAVs could present even thornier questions. Currently, most large drones are heavily automated to allow them to complete tasks, but they still maintain a connection to a human operator. A good example of that are commercial airplanes—they are automated with pilots monitoring the activities of the autopilot system, which is designed to fly the plane for most of the flight on its own.

The brave new world of drones includes a not–too–distant future where those computers and devices will evolve from automated to autonomous. They will be designed to make some decisions on their own, without human input. A similar autonomous design will likely be used in Google cars to effectively operate on city streets, experts say, although no one has produced the more sophisticated artificial intelligence to make it happen.

“UAVs today are heavily automated and not autonomous,” Cummings said. “The more guessing you have to use in a situation the more autonomy that you have. We are giving these systems the ability to reason on their own.”

Cummings said she knows of a case where a Global Hawk, the airliner–sized drone for U.S. military surveillance, lost its link to its operator but was successfully able to land itself. If the UAV loses connection, it is programmed to continue to its destination or return to its point of origin and land. First introduced in 1995, the jet–powered Global Hawk flies for more than 30 hours at a time at altitudes of up to 65,000 feet. It can monitor an area of about 40,000 square miles.

Autonomy for machines is a daunting notion, one that could create circumstances that would strain the legal tools available to both monitor and govern drones and their evolution.

Industry leaders say UAV technology is too young and too beneficial to society to leave it idling on the runway because of public fear of the future or overstated threats to privacy and safety. They say all of these issues can be adequately addressed through sensible, even-handed regulation and licensing.

Not everyone is so sure that the pace of technology will allow the government and the public the breathing room they need to contemplate the future, and then to adequately regulate the technology where it touches humanity.

We are shoveling against the tide of intrusions by technology into our privacy and our lives, says Fishman, the law professor at Catholic University of America. It’s still worth the effort. As much of our privacy or our lives as we can reasonably protect for as long as we can, it’s worth the effort.

Resources:

-

Washington Lawyer: July/August 2013 – The District of Columbia Bar

-

AF Law Review vol. 70 – Air Force Judge Advocate

-

Sarah Kellogg, Washington Lawyer Magazine, May 2011, 7 pages

-

DHS/NPPD/PIA-002 Automated Biometric Identification System

-

The Drone Next Door | NewAmerica.org

-

Rare CIA Propaganda Leaflets Dropped in Laos during the Vietnam …

-

Drones Over the Homeland – Center for International Policy

-

The Drone Question Obama Hasn’t Answered

-

Are ‘Self-Defense’ Drones Protected by the Second Amendment …

-

National Defense Authoriation Act (NDAA) | lisaleaks

-

Drones: A rare glimpse at sophisticated US spy plane

-

What you don’t know about Google’s self–driving cars

-

A future for drones: Automated killing

-

DARPA: Hybrid Insect Micro Electromechanical Systems (HI-MEMS)

-

Autonomous Drone Research

Related articles

- Police Surveillance Drones Pose Threat To Domestic Privacy (mysecuritysign.com)

- Drone Home: Eyes in the Sky and Privacy Concerns on the Ground (acslaw.org)

- Federal government ‘lacks a clear policy’ on use of drones by law enforcement (o.canada.com)

- Drones to surveil US population by 2015 (hangthebankers.com)

- Nuclear UAV Drones Could Fly for Months at a Time (backcountryvoices.wordpress.com)